Recognizing Elements of Patient Non-Compliance

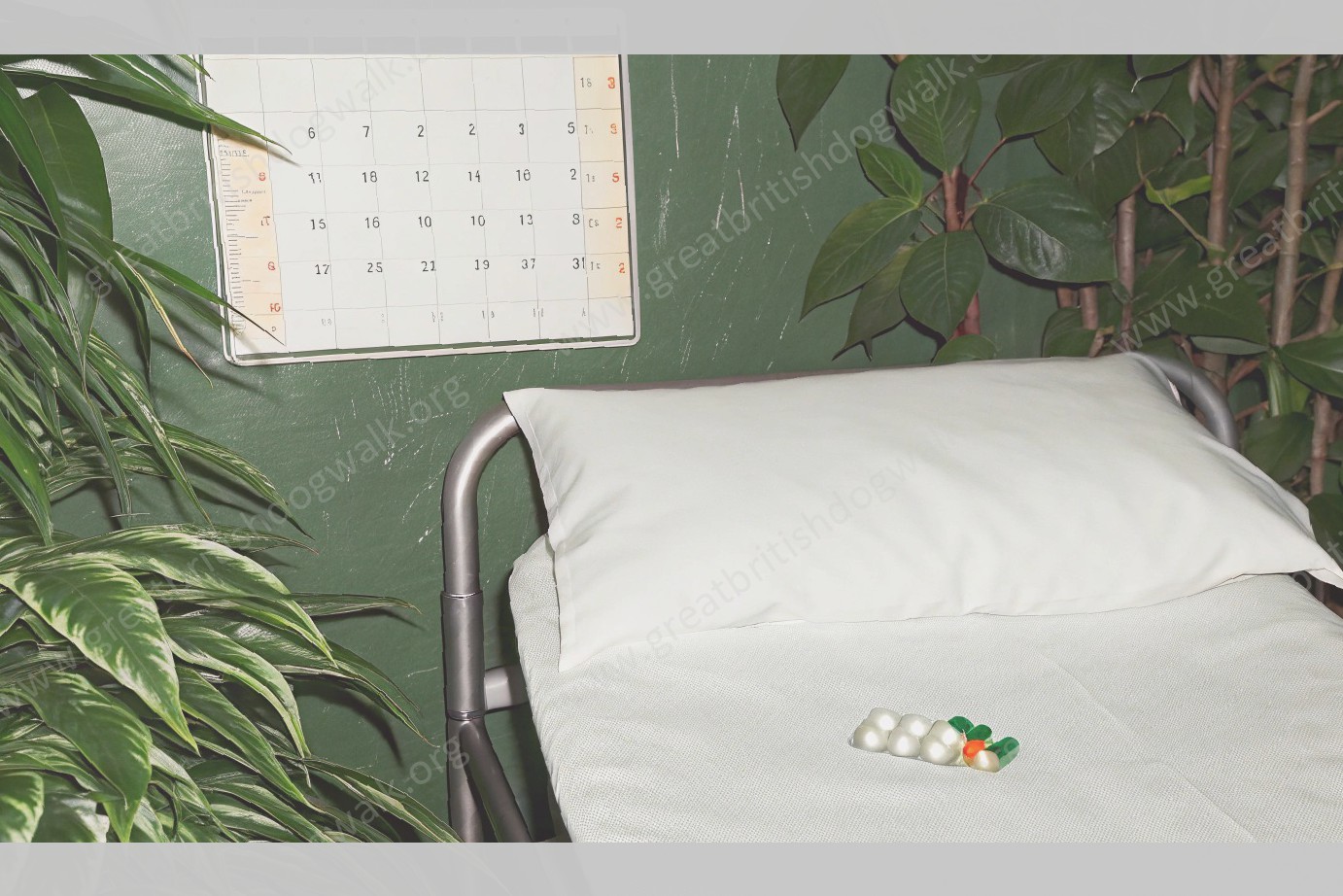

For a patient to demonstrate non-compliance, in addition to being conscious and aware of their medical obligations, they must also actively ignore them. The most obvious choice for an example of this is a patient that refuses to take life-saving medication, such as insulin or heart medication, but denial of treatment also counts as non-compliance. For example, a patient suffering from a severe bacterial infection that fails to fill a prescription for antibiotics or that refuses to stay on topic at a follow-up appointment so that they can ask about romantic endeavors instead might be considered non-compliant with treatment that their physician indicates they need. A patient laying in a hospital bed and refusing to fight through rehab in order to leave, or one that refuses to come back in for a follow-up visit after having a leg amputated and instead just stays at home, would also be non-compliant.

A more nuanced example is someone that misses medical appointments. Although there are many reasons that someone could miss an appointment — traffic, childcare difficulties, illness, forgetfulness, etc. — it’s still a fair question to ask whether a person that misses their doctor’s appointments is being non-compliant. The general answer is that someone that lets their appointments lapse slowly over time doesn’t count as being non-compliant , since that could indicate a lack of motivation or mobility rather than a conscious refusal to follow their doctor’s orders. But a patient that shows up to appointment after appointment and refuses to follow the protocol does.

A critical case on this point is the Alaska Supreme Court decision in Stokes v. PHS Medical, Inc., which involved a patient that did not follow his doctor’s weight-loss protocol, meaning he was prescribed Phentermine but failed to take the medication. In his first three visits to the doctor, he weighed an average of 598 pounds and was prescribed the drug. During the next two visits however, he refused to take the drug because he felt it was ineffective. He went to his final two appointments at well below 500 pounds, and the plaintiff argued that the loss of weight at such a substantial size was proof enough that he had no alternative motivation for visiting the doctor than to be given the drug and receive insurance benefits from PHS Medical, Inc., which required the prescription of this drug. The Supreme Court found that the jury could reasonably interpret the first two patient visits as evidence that the patient was not complaining, as noted, and that likewise they could reasonably interpret the second two visits as evidence that the plaintiff was non-compliant. However, the court noted that the plaintiff was within her rights to discontinue taking the drug if it was having no effect and that doing so would not mean she was non-compliant.

Legal Responsibility of Health Care Providers

The legal obligations of health care providers include a duty of care to their patients. Duty of care is a legal concept that obliges a health practitioner to take reasonable care to avoid predictable harm to a patient. If a practitioner is negligent in this duty, for example by failing to provide treatment as a consequence of the patient’s non-compliance with the plan without warning, the practitioner may be liable in medical negligence (aka personal injury) litigation.

Medical negligence claims between doctors and patients are in large part based on a doctor’s duty of care to take reasonable care to avoid risks of harm that would be apparent to a reasonable doctor. That includes a duty to warn the patient of the risks of harm associated with their treatment and of their non-compliance with it. If a patient ignores that warning, then the duty of care otherwise owed may change in some circumstances as a consequence of the patient’s exercise of free will and determination to disregard the risk under the circumstances, but this will depend on the circumstances.

The first step in making out a medical negligence claim is to establish that the doctor owed that patient a duty of care. There will be no duty of care if the doctor is a stranger and a chance meeting where a patient assails the doctor with an emergency constitutes that patient as a voluntary patient.uch should avoid.

A doctor caring for a voluntary patient who has capacity will not be liable for a patient becoming ill but what if the patient refuses treatment or fails to comply with it; can the doctor be liable then? The answer is also not clear-cut. In the case of such a patient, the doctor’s duty of care and legal liability boils down to whether the doctor gives the patient adequate information about the risks associated with the patient’s voluntary decision to reject medical advice and declines to comply with the doctor’s treatment plan. In such a case where the patient suffers harm, the doctor may be liable in negligence.

In determining the appropriate standard of care, which is a question of fact, the court takes a flexible view based on the unique circumstances of each case. They will consider:

Failure to warn of the risks of a patient’s decision to decline medical advice and treatment may amount to a breach of duty of care and may amount to a failure to properly inform a patient, in a legal capacity, of the risks of harm that would be apparent to a reasonable medical practitioner. The risk must be obvious to the patient, known to the doctor, and the patient must have the capacity to understand the risk. However, those circumstances must be judged on a case by case basis and when applying a flexible standard of care to the circumstances surrounding the patient’s failing health and their refusal of treatment, the patient’s autonomy and right to self-determination needs to be considered alongside the doctor’s duty of care.

Potential Legal Implications for Patients

With advancing modern medicine and opportunities for healthcare to be more personalized, there has been an increasing concern over patients’ failure to comply with healthcare provider’s advice. Once patients fail to follow healthcare providers recommendations, the concern shifts from whether the medical decision was correct to whether the patient should be deemed responsible for their own health failing. If a patient fails to follow the instruction and advice of an appropriate physician their non-compliance can be seen as contributing to the problem or condition which they are suffering from.

Withdrawal of Treatment is a potent legal consequence to a patient’s breach of their duty to care. If a healthcare practitioner who has previously agreed to provide a set level of care feels that further treatment by the healthcare practitioner would be pointless, the healthcare practitioner may be authorized to withdraw treatment. If there is reversal of the last patient-physician encounter, there is an affirmative duty of the healthcare practitioner to set forth the reasons for withdrawal as well as documenting the refusal of the patient to provide such information. In the alternative, if the withdrawal of treatment was abrupt, the patient may be entitled to damages as the physician is legally required to provide sufficient notice and reasonable opportunity for the patient to obtain alternative care. For an instance of physicians withdrawing treatment, reference the decision made in Groover v. Walker General Hospital, Inc.

Another legal implication of non-compliance is the potential loss of insurance coverage. A prudent action of an insurer is to use a patient’s non-compliance with the physician’s plan of treatment against the patient. This means that if an insurance company deems that a patient was eligible for treatment under the following provision, "non-compliance, [is] resulting in failure to complete course of treatment," they may deny the patient liability. However, this may not always be a strong point for insurance companies in the event of a legal dispute, as most courts find that "an insurance company cannot deny coverage based on "insufficient medical necessity without expert evidence supporting the denial."

The Impact of Informed Consent

Patients who are non-compliant with their treatment or practice providers are usually viewed as a liability. Legally they can be. Your course of action with them can protect you from major liabilities, and it can also protect you from them possibly haven’t been sued by them later on down the line. As I mentioned earlier, many people participate in care that they may not understand or completely agree with. Usually informed consent is the way to go if you want to protect yourself from this situation.

"Information" is the key word. It does not mean that the patient understands everything that is being done, only that they have been informed of the proposed treatment and its attendant risks, benefits, and alternatives. Informed consent is concerned with what the patient knows. The patient is the one to whom the information is given and is the one that is supposed to receive it. The patient does not require an education or explanation of the proposed treatment in order to consent to it . On the contrary, the patient is cured of his ills by the treatment, and the doctor brings the appropriate knowledge to the sick room, removing the patient’s need to know.

The informed consent form is designed to inform the patient so that the practitioner can be protected legally. The form should cover everything possible that could "bite back", and list the known risks and complications of the proposed procedure. The patient has a choice of consenting to the proposed treatment or refusing it. Informed consent covers all types of health care providers, and can apply to almost any type of health care procedure. Keep in mind, however, that informed consent is an ongoing process. The practitioner must keep talking to the patient about the procedure and answer any question. The informed consent form should clearly state that the consent was given of the patient’s own free will and without promises or pie-in-the-sky information. If the complexity of the procedure warrants it, the recommended approach is to have the patient sign two different informed consent forms, one for each side of the situation.

Handling Non-Compliance

Health care professionals should understand the commonalities and factors related to patients’ non-compliance and develop appropriate strategies to successfully reduce non-compliance in their practices. These strategies may be effective in improving patient compliance, but the most significant benefit is that they may help limit liability.

In response to questions regarding methods to increase patient compliance, study authors Weston P. Jackson Jr. and William R. Holden provided an evidence-based review of the literature. They analyzed the studies under four methods of increasing patient compliance.

First, the authors studied provider education and how information distributed to patients through pamphlets, books, and videos could help patients better understand the conditions or risks they face, and encourage them to follow treatment plans.

Second, the authors studied provider reminders, which they stated increased compliance in some studies up to 81 percent. Such reminders can be delivered to patients by phone, mail, or during their office visits.

Third , the authors studied the effects of financial incentives on patients’ compliance rate. The studies reviewed indicated that as the amount of the incentive to comply increased, the patients’ compliance increased, but only to an extent. However, the authors concluded that health care providers should also be aware that patients receiving financial incentives for compliance may be more susceptible to harm if the providers fail to meet the standard of care.

Fourth, the authors stated that reinforcement, which includes parental modeling and discipline, can also increase compliance. After reviewing these studies, Jackson and Holden stated "by implementing a program that is focused on patient education and education of healthcare staff regarding compliance concepts, healthcare practitioners may be able to significantly improve patient compliance, which may subsequently reduce malpractice liability."

Depending upon the particular issue at hand, clinicians may rely on any one of these methods, or a combination of them, to increase patient compliance, and reduce risk of liability.