What is a Build Transfer Agreement?

A build transfer agreement is a contract that outlines the terms and conditions of ownership on a building project after a developer completes its work. This agreement is primarily used in the context of construction and real estate transactions to define the relationship between the developer, who is building the property, and the buyer who is purchasing the finished property. The purpose of a build transfer agreement is to set forth the responsibilities of each party in the transaction and to ensure a smooth transfer of the constructed property once completion is reached. Specifically, a build transfer agreement will typically contain provisions detailing the parties’ obligations for payment, construction milestones , warranties, indemnification clauses, and the transfer of title and/or occupancy of the real estate once it is built. Other common terms that are included in build transfer agreements include, without limitation: Dispute resolution provisions; Post-closing obligations; Deliverables; and Liabilities.

Build transfer agreements differ from other types of agreements in that they are often used in connection with a long-term ground lease relationship between the buyer and seller. Thus, typically, a build transfer agreement will only make sense once the ground lease has been executed and granted. The laws and application of build transfer agreements vary by state and can be impacted by the type of project being developed.

Key Elements of a Build Transfer Agreement

In general, the fundamental elements of a Build Transfer Agreement (BTA) are similar to those of a project construction contract. The parties to a BTA need to be absolutely clear on the scope of work, cost, schedule, and other primary areas of focus.

Scope of Work

The scope of work to be performed under a BTA defines the obligations of both parties. For example, the scope may clearly identify which contracts or subcontracts will be transferred from the Builder to the Buyer. The scope of work provisions of the BTA also may delineate issues such as which party is responsible for utilities, performance testing, or the costs of design revisions that occur after the execution of the contract.

Schedule

The schedule component is at least as important in a BTA as in a construction contract. There are many possible complications and changes to the work that can affect the project schedule, and the cost implications of working around such issues likely would be significant. The buyer and the builder must agree on the specific milestones and completion dates for the project. Under a BTA, the schedule may differentiate between long lead items, and elements for which the manufacturer has not started production. The schedule provisions of the BTA might clarify expectations such as when a product will be delivered to the job site or when a subcontractor will mobilize at that site.

Cost of Work

The method of payment under a BTA differs from a standard construction contract. Typically, the builder is entitled to progress payments based on the percentage of completion of a project. Under a BTA, the builder continues to receive progress payments for the work that it is performing, but then may have rights to additional payment adjustments for the work it has transferred to other entities. The BTA can draw payment lines between the work performed by the builder and that which is performed by its contractors and subcontractors, or the BTA can provide for separate payment terms for each element of the project.

In addition, the BTA will have provisions to determine the price for any options the buyer decides to take after signing the BTA. Adjustment clauses will allow the owner to make changes in the specifications or drawings, or to add or delete work without interfering with the completion of the builder’s work. The price and payment adjustment provisions also should address situations in which actual measurements significantly differ from those in the plans and specifications.

Other Potential Clauses

A BTA may include numerous other provisions. For example, it may require the builder to permit the buyer (or a third party acting on behalf of the buyer) to enter the job site to inspect the premises during all phases of the work. It may require the builder to carry builder’s risk insurance, and give copies of all policies and all notices of default to the owner. The parties also may choose to indicate in the BTA whether the executed agreement transfers the project as a single entity, or in parts, or by systems.

Other potential provisions can include clauses that state the applicable law for the BTA, require the parties to mediate or arbitrate disputes in the case of a problem, and others. The most appropriate provisions for any BTA depend on the project, the parties, and their preferences.

Benefits of a Build Transfer Agreement

Using a Build Transfer Agreement provides a number of advantages for both the developer and the property owners. As a developer, it allows for greater control of the budget because the handover of the works will only occur once the works have been completed in accordance with the requirements set out in the agreement. Therefore the developer will only be responsible for executing all of the works in accordance with the requirements of the agreement because they will not be able to transfer title until they have complied with their obligations.

For a property owner, it can provide greater certainty as to the costs associated with executing the works. In many instances, the costs form the basis upon which the lease or licence is granted to the developer or lessee and having certainty as to what those costs are is a significant advantage.

The Build Transfer Agreement is also a very useful tool in managing the allocation of risk on large-scale projects. For example, most construction contracts will have a defects liability period which requires the development to be remedied if there are faults in the construction. In some instances a property owner may want to assume the risk for those defects and the Build Transfer Agreement can provide for that.

Common Challenges and Resolutions

The agreement must address how the works will be handed over from the contractor to the client, from the client to the end user and from the end user to the operator. This needs to include an assessment of whether utilities and other users will have uninterrupted access to the buildings, so that their day to day operations are not adversely affected.

Developments are invariably carried out in phases and parties must ensure that the arrangement takes account of the full range of modular units on site and they have co-ordinated their programming and ordering to ensure that the handover is seamless.

The transfer of risk between the parties requires careful consideration. In light of the risks that the client will take on, the price payable for the works must be determined in a way which reflects that level of risk and provides the contractor with sufficient incentive to comply with its contractual obligations. The two elements generally examined are the use of liquidated damages (LDs) and/or retention, both of which need to be considered in the context of financial forecasting and the financial strength of the contractor. Retention can be more attractive than LDs as it reduces the risk that a client might end up paying LDs if the works go into delay, when it cannot actually measure the loss it has suffered.

Another common issue that arises in the context of construction fees and payments, is the timing of payment, i.e. when is payment of the whole or any part of the contract price due? The default position is that the contractor is entitled to receive at least 95% of the contract price when the works have been delivered/installed; and the remaining 5% either at Practical Completion or after a short period of time has passed to allow the contractor to carry out snagging works. However, depending on the stage of the project and the risk profile (and bargaining strength of the contractor) these milestones may not be suitable (e.g. if the works are delivered and installed early), and the parties may need to consider some more bespoke mechanism to pay the contractor.

Build Transfer Agreements often involve contractors who belong to a large group of companies. This can lead to issues in relation to security if, for example, the parent company causing the contractor delays significantly, or if the contractor is acquired by another company which is unable to fund the works or to juggle funds. An appropriate solution to this problem is to ensure that an Event of Default occurs if change of control measures do not occur.

Legal Considerations and Compliance

Commercial arrangements involving statutory and regulatory approvals are not as common as a full build project where statutory approvals are required. From a legal perspective, parties must check whether an approval is needed for the relevant topic and whether the approval must be granted by a particular local authority. Where a code requires a particular service provider (such as a utility company) to be involved, that service provider must be consulted prior to contract execution.

How each agreement describes the transfers of the build assets is also important. In the absence of clearly set out terms, approval may be implicit, resulting in damaging delays and liability.

Similarly, if the approval is expressed to be given upon delivery of the entire facilities and not a milestone, this may result in the entire contract being a default in respect of one defect. It is also customary to reserve the approval right to the relevant local authorities and all affected third parties , for example, utilities and other service providers, in order to properly manage utility and service connections.

Joint development agreements are common where two or more parties undertake the development jointly and concurrently along with a government body. Each such agreement has specific requirements for proper joint management, which usually deals with each parties’ rights and obligations in relation to the project design, construction and delivery of the facility, and acceptance and commercial operation of the facility.

Generally, the local authority responsible for the area facilitates the project’s development, providing regular updates and reporting to government. In practice, liaison with the local authority is an ongoing process, and guidance from the local authority will be necessary during the course of the development.

Parties should consider whether South Africa’s participation in international treaty obligations may require amendments to be made to the agreement.

Recommendations for Successful Implementation

Establishing a clear and open line of communication between all relevant parties is crucial to the success of a BTA. Both the buyer and seller must be aware of each other’s expectations and requirements going forward. For example, for the transition from a process flow diagram in the contract to the written procedures, it is important that both parties understand the format of the required written procedures (length, level of detail, etc). The seller should not be surprised when the buyer requests several revisions to the written procedures if the buyer did not clearly express what was desired at the outset. Similarly, while transparency to the seller is generally a good business practice, a seller may legitimately want to limit its exposure in certain processes (such as change control) during the transition period. In addition to clear communication on specific requirements, there should also be a mechanism for ongoing opportunities to raise questions about the BTA in general. This is particularly important if the entry of a new product is anticipated in the near future. The process by which the contract will be interpreted and managed in order to accommodate the new product should be documented in advance. Keeping the BTA mgmt. committee apprised of progress on the BTA implementation task list is vital to making sure that nothing falls through the cracks. Because the implementation of a BTA is usually the most time-consuming and complicated aspect of the transaction, diligence and attention to detail is especially important. To ensure a smooth transition, it is essential to be able to document that: The seller must be diligent in following both the contract and its own internal procedures. The buyer should remain actively involved by providing questions and comments on the procedures and maintaining a vigilant eye on change control and capacity planning and forecasting documentation.

Case Studies: Practical Examples

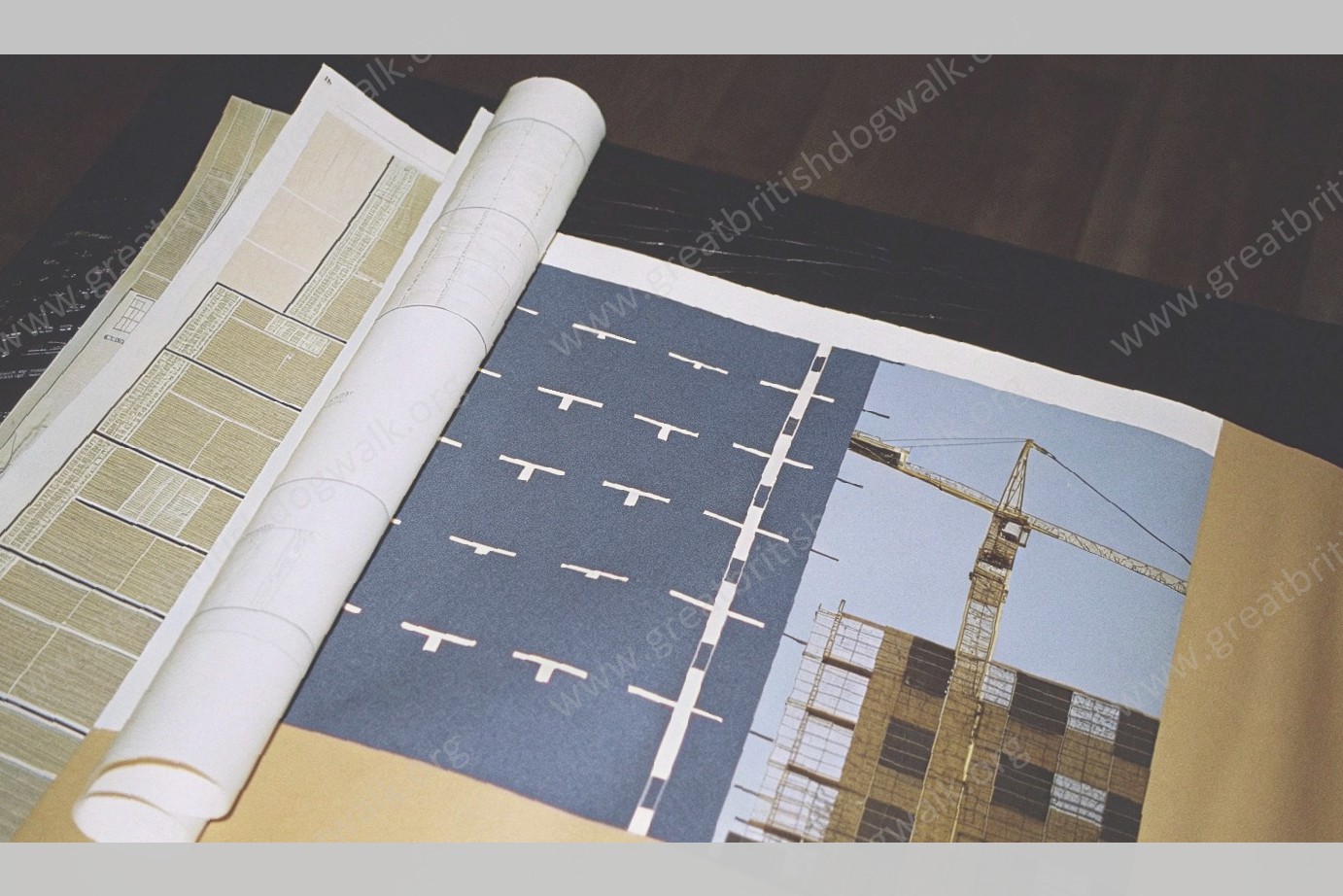

The use of Build Transfer Agreements is not exclusive to any one sector or industry. They are common in a variety of practice areas such as construction, technology and healthcare. Below are two examples of how Build Transfer Agreements have been employed in the real world.

In 2015, North Carolina Cancer Hospital (now the N.C. Cancer Hospital at UNC Hospitals) was undergoing a massive expansion to accommodate an aligned increase in patient volume. A partnership that was formed in the 1970s produced the ground-breaking research that allowed them to offer early experience in high-dose chemotherapy with autologous hematopoietic stem cell rescue for patients with diffuse large-cell lymphoma. Many local, national and international treatment centers have since emulated their model. As a reward for their work, the N.C. Cancer Hospital was awarded the 2012 Outstanding New Hospital Award by FGI (the Facility Guidelines Institute). Their outstanding research reputation and phenomenal patient care experiences attracted increasing numbers of clinical research trials in oncology and greatly impacted their success. Additionally, their growth spurred an increase in the size and scope of the clinic’s programs.

This, in turn, contributed to doctor retention and expansion of new oncology programs by attracting some of the finest cancer specialists in the world to the Chapel Hill area. With that success, however, came challenges. N.C. Cancer Hospital no longer had enough room. Its existing footprint proved to be a limiting factor in its effort to add more clinical space to support new clinical trials, expand the referral base, accommodate its growth in clinical services and provide its growing research programs with the necessary space, equipment and staff to achieve their desired results.

Howell, as a member of the board of directors, found himself at the center of the problem, quickly becoming the recipient of several complaints from doctors, nurses and administrative personnel. He met with the CEO and project manager on numerous occasions to discuss their frustration with the limited purpose of the renovation process and to advocate for a more holistic approach. However, Howell found that the people he met with were reluctant to explore a more expansive study of the issue. Without action , staff morale declined and the number of accomplished doctors leaving the hospital soared. Stranded between his commitment to his own firm, which was responsible for the acquisition of the project, and his advocacy for the hospital, Howell chose to escalate the issue to the board.

Howell formulated a plan to solve the issue. He proposed an original agreement and proceeded with its presentation. During his initial discussions with the board, Howell explained that the project plan should be adjusted, and negotiated a more flexible and effective approach. Howell then explained to N.C. Cancer Hospital that the initial strategy would have unnecessary negative impacts on all activities and cause the program to fail long term. Finally, the board decided to change its focus away from an aggressive building process, and the plan was adjusted accordingly. In an epic turnaround, with the decision to expand the study and examine the entire Campus Plan, N.C. Cancer Hospital underwent a complete academic growth spurt.

Penn Medicine, which already had real estate interests, was considering the acquisition and renovation of a new hospital facility in Secaucus, New Jersey, which was up for sale at a reasonable price due to financial instability. As medical services in New Jersey face consistent downward pressure from changes in reimbursement for Medicare, Medicaid and managed-care programs, expanding outside of Pennsylvania was in Penn Medicine’s long-term interests.

Jay DeLaney and his partner were tasked with reviewing the potential acquisition, and thus began their due diligence and status assessment. They spent several days meeting with key executives & staff members, reviewing financial statements and touring the hospital. After months of review, including review by Penn Med’s legal counsel and insurance brokers, the decision to proceed was made. Detailed contracts were proposed and negotiated, taking into consideration the sellers’ needs, and despite resistance from the sellers (they did not see the benefit of a Build Transfer Agreement), all concerns were addressed and the deal was made. Today, Penn Medicine has fully integrated Hackensack University Medical Center into its system and makes "N.J." a letter in its brand (Penn Medicine New Jersey).