An Overview of Space Law

As humankind’s activities in space have increased, so too has the need for regulating and managing what many see as mankind’s "next frontier." The frontier of space has become a busy zone of scientific research, experimentation, exploration, and development. Launching, operating, transferring, and dismantling spacecraft in space has become the norm for both governmental and private entities. As a result, a complex and comprehensive body of international and domestic law has emerged to govern such activities and resolve disputes between stakeholders. Space Law now consists of numerous treaties and conventions which govern various aspects of international space activities. Currently, there are five overarching treaties that govern space law: the Outer Space Treaty; the Registration Convention; the Liability Convention; the Rescue Convention; and the Moon Agreement. In addition, a number of United Nations General Assembly resolutions set out the General Assembly’s view on various aspects of space activity, including the benefits of international cooperation, the peaceful uses of outer space, and such principles as the "common heritage of mankind" and "solidarity . " Space Law also includes the many national laws that have been created and implemented to regulate both foreign and domestic entities conducting business and operating in space. For example, in the United States, the National Aeronautics and Space Administration ("NASA") is responsible for the promulgation of its Space Act and the Commercial Space Launch Federation Act. NASA and the Federal Aviation Administration (a division of the Department of Transportation) are also responsible for issuing commercial launch permits. The Federal Communications Commission licenses satellites and provides regulation over respective radio frequencies and geostationary orbits, while the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (under the Department of Commerce) is responsible for the licensure and regulation of private meteorological satellites. Space Law is an ever-growing body of domestic law, international treaties, and commonly accepted practices that have developed in conjunction with the new industries and endeavors that have emerged as a result of activities and advancements in space. Experts and practitioners alike have only begun to understand, analyze, and apply the myriad of laws affecting stakeholders in this rapidly expanding field.

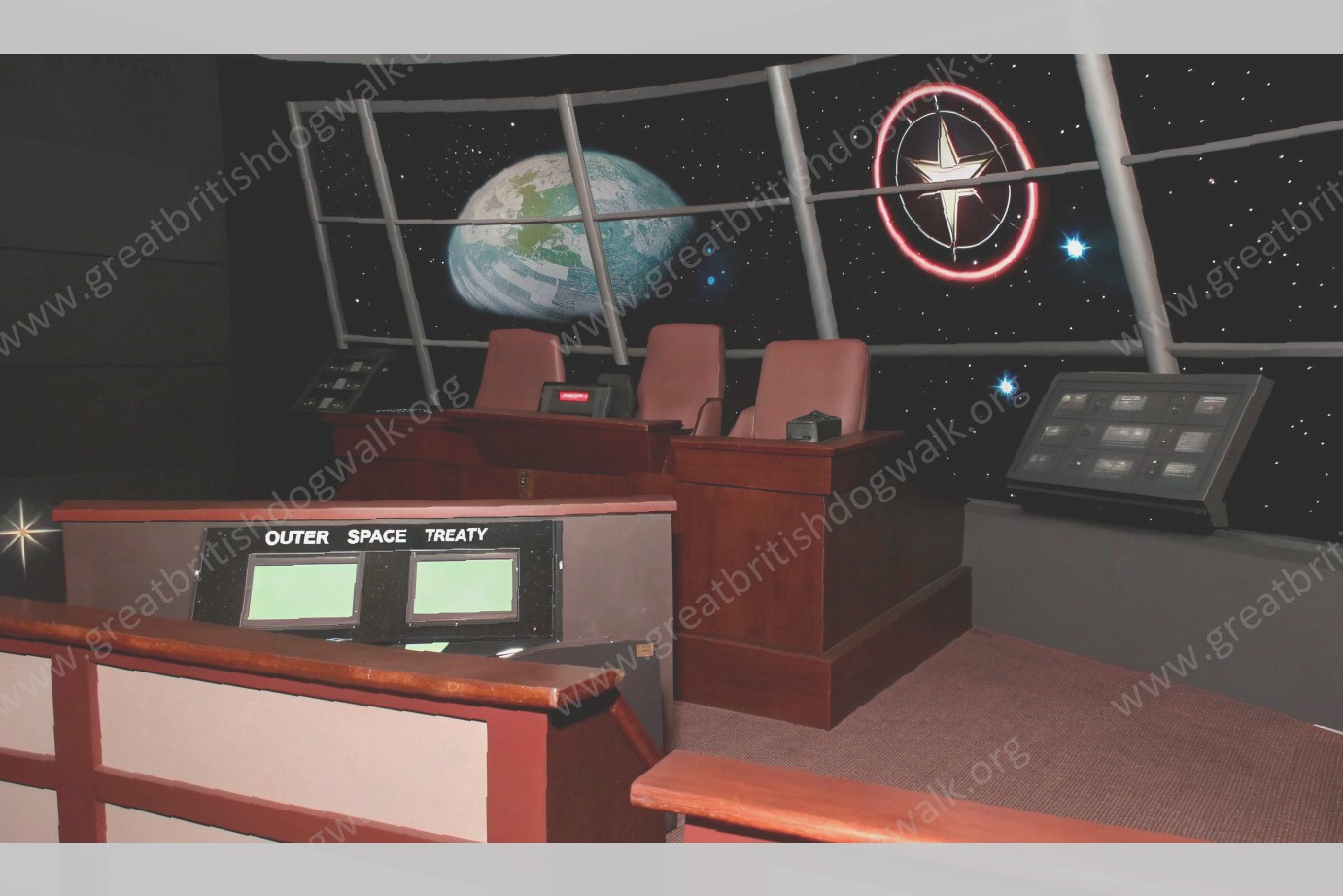

The History and Influence of the Outer Space Treaty

The 1967 Outer Space Treaty, or the "Treaty on Principles Governing the Activities of States in the Exploration and Use of Outer Space, including the Moon and Other Celestial Bodies" is frequently referenced as the framework for space law at the international level. It is a result of much international collaboration and offers binding guidance on activities in, and with respect to, outer space.

The Outer Space Treaty was drafted with the intent of deterring the militarization of space and facilitating cooperation amongst the parties. The Outer Space Treaty has been signed and ratified by 110 countries, and 23 additional countries have only signed it.

Its main relevant provisions are as follows:

The treaty has had a lasting impact on the way that various contemporary space law cases have been decided. For example, the ideas of "freedom of exploration" and "non-appropriation" have been cited as justification for the legality of space tourism and space resources exploitation. Of course, more recent non-binding UN space law measures complement the Outer Space Treaty well. It is anticipated this will continue to be so for future developments in space law.

Deep Space Liability: The Case of Cosmos 954

One of the most glaring examples of space liability issues is the case of the Soviet Union’s Cosmos 954. On January 24, 1978, the Soviet Union’s satellite fell over an area of Northwest Territories Canada due to a steady loss of altitude within the spacecraft and within a few minutes crashed into the earth at a site now known as the "Cosmos 954 Crash Site." The Cosmos broke into many pieces. The most remarkable of which was a very radioactive reactor core recovery by the United States Air Force, Canadian Armed Forces and the Royal Canadian Mounted Police. Domestic and international litigation resulted from the accident and has had a long-term impact on space law. The initial treaty negotiation for damages between Canada and the Soviet Union was incomplete, and additional bilateral negotiations took place between Canada and the United States (U.S.), as the Cosmos collided into both countries.

For the purposes of national security and environmental concerns imposed by the U.S. Air Force and the Canadian Government, the reactor core recovery efforts were kept a secret for more than a year and the details of the settlement were not revealed until years later. Part of the settlement included a pledge to destroy remnants of the nuclear material from the reactor by the United States. Another space law consequence was the adoption of international policy guidance in 1982 by the Committee on Long-Term Sustainability of Outer Space Activities. The Cosmos incident launched a sublicensure agreement in which the USSR could no longer use RTX items in any other Russian state party territory. Innovation continued through the commercial space age with service-based models for satellites. The value of commercial space communications has exceeded $3 billion dollars over the last forty years since the incident. The Cosmos 954 incident in the Arctic had an impact on the growth of the Aurora Borealis Bond Proxy and the first suborbital reuse technology to launch and return after examples of the space shuttle system.

Outer Space Intellectual Property Rights

The issue of intellectual property rights ("IP Rights") in space gained traction in 1999, following the first successful sync-sat launch conducted in May 1999 by Iridium, a telecommunications company. Despite the absence of any legal framework of reference, the focus on this issue has continued to grow steadily over the years.

The application of IP Rights to inventions owned or controlled by private individuals or entities engaged in space activities is particularly complex, as the determination of the law applicable to such IP Rights relies heavily on the applicable law of a territory and/or jurisdiction, thereby requiring, for instance, the resolution of forum-shopping disputes or sub-forum issues.

The fact that the Outer Space Treaty contains express provisions relating only to public goods and services, such as the regulation of radio frequencies used by satellites, implies that private individuals or entities engaging in space activities are not expressly entitled to IP Rights, which leaves them and numerous space start-ups to rely on national legislation for adequate protection. Such protection is becoming all the more relevant as sophisticated technologies developed in space industries find application on Earth, given the increasingly blurred lines between Earth-bound and space activities.

This point was highlighted by the BlxLoc case, a US court case in which the plaintiff, a satellite manufacturing and launching company, brought a claim alleging infringement of its patent for a satellite navigation technology. The US District Court for the Southern District of New York granted the company an injunctive relief order to restrain the defendant’s use of the accused navigation method and devices, based entirely on US patent legislation. The question raised in the case was whether the purpose of the patent protection was being achieved outside of the jurisdiction, in this case the US. The court concluded that the manufacturer’s satellite was utilized for navigation and other purposes in countries other than the US, while the defendant produced a product that directly competed with the plaintiff’s patent.

The expansive definition of the notion of "space object" under the Outer Space Treaty, namely, any "human-made spacecraft which has been or is intended to be launched or placed in outer space", means that virtually any object launched into space may be classified as a space object. Both US and international IP Rights law necessarily therefore rely on an analysis of the location and the manner in which these objects are produced.

In a bid to adopt a more integrative approach towards IP Rights, leading space countries and organizations have implemented legislative reforms that more expressly cover IP Rights in space. A noteworthy example is the Outer Space Activities Bill 2014-15, which was introduced by the Australian government into the Australian Parliament on 26 November 2014. Pursuant to its terms, the Bill amends current space legislation to redefine the IP Rights of private space ventures (source: Mondaq).

Moon Agreements on Sovereignty and Resources

The Moon Agreement has been the subject of much debate since it was drafted in 1979 under the auspices of the United Nations Office for Outer Space Affairs. A fundamental tenet of The Moon Agreement is that the Moon and its resources are the "common heritage of mankind." In other words, no state may appropriate it or its resources for commercial use, and all endeavors on the Moon must be undertaken for "the benefit and interest of mankind."

The Moon Agreement presently has only 18 parties, far fewer than the 104 that ratified the 1979 Convention on Registration of Objects Launched into Outer Space. It is considered a failed treaty, and many believe that it will become no more than a footnote in history.

The Moon Agreement is also considered broadly defined, with some provisions that are incongruous with the general spirit of international cooperation. For example, the agreement calls for states to set up an international regime to govern "activities in the exploration and use of the Moon, including the establishment of international guidelines regarding activities in the Moon so as to avoid their harmful contamination . . . ." Article 11 similarly provides that when a state engages in commercial exploration, it must compensate other states that carry out exploratory activities. Critics assert that it is not necessary to employ such vague language in order to call for an international regime in space, an arena in which nations work cooperatively.

Notably, states that have yet to ratify the Moon Agreement comprise a large majority of the spacefaring nations. These include major spacefaring states such as the United States, China, India, Japan and Russia .

Despite the fact that the Moon Agreement was developed over thirty years ago, resource mining in outer space is a hot topic in international space law due to a series of key cases and ongoing legal debates. An early example is the dispute between the United States and the Soviet Union over the right to explore and exploit resources found in Antarctica. In 1972, President Nixon signed the Antarctic Conservation Act, declaring that the Outer Space Treaty applied to actions in the Antarctic, including the possibility of mineral exploration. In 1976, the U.S. responded to USSR’s assertion of sovereignty in the Arctic with its own claim in the Arctic in the case re United States v. Alaska.

Contemporary cases addressing the issue of space resource mining include two near-simultaneous cases from April 2012. Planetary Resources, Inc. and the Licensing Board of the U.S. Federal Aviation Administration consider the definition of space activities and whether mining resources from asteroids qualified as such. In both cases, the respective administrative boards decided that asteroid prospecting was indeed a space activity. Their decisions also rejected the argument that planetary prospecting intended to establish criteria for the appropriation of resources by private entities.

Although there are presently no finalized treaties that directly address the issue of mining resources on celestial bodies, spacefaring nations continue to strive to develop policies that will regulate outer space within the rule of law. Such efforts may require these states to breach the long-standing traditions of legal non-appropriation of celestial bodies and the common heritage of mankind or the agreement of several space nations to develop a new legal regime that benefits humanity as a whole.

SpaceX’s Controversial Endeavor

Commercial enterprises are no strangers to the sphere of space exploration and exploitation. From spacecraft manufacturers to satellite operators, competition in the private sector is quickly escalating the historical pace of space activities. However, with increased activity in low-earth orbit (LEO), significant legal challenges will arise when novel space activities occur in close proximity to residential areas, migratory routes, or ecologically sensitive environments.

These types of environmental factors may be limited to Earth or may be encountered by space activities anywhere in the solar system and beyond. Either way, several notable space law cases involving commercial space companies will test the limits of their individual and cumulative environmental impacts on Earth, on interplanetary transit routes, and on the Moon and Mars.

SpaceX has experienced its share of challenges from federal agencies and environmental groups. Environmental impact analyses, debris mitigation requirements, mitigation of launch-induced noise, and even congressional interests are some of the hurdles SpaceX confronted in order to launch commercial and government payloads. In one case, a practice and demonstration Environmental Impact Statement (EIS) was required to assess the site location and launch schedule for SpaceX’s Falcon 9 rocket. Both the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) and the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service (USFWS) requested extensive information related to the EGAD site and launch schedule. The USFWS cited seabird populations and potential migratory bird strikes and requested an assessment of "launch noise and NOTAMs on the occurrence and dispersal of migratory birds." NOAA was concerned with "detail steps to be taken to avoid creating marine debris as a result of items falling into the ocean as part of the planned mission."

Further requirements also emerged from SpaceX’s resupply contract with NASA for the International Space Station (ISS). The National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) required NASA to conduct a Programmatic EIS (PEIS), with SpaceX being a sub-contractor in the process. The PEIS not only assessed impact of the launches on the planet but also on low-earth and mission orbits. The biggest surprise in the EIS process was that it sought punishment for what the NASA/USAF EIS considered a "de minimis" amount of rocket fuel particles left in the middle and outer orbits after Falcon 9 launches. Other examples include ESA’s study of noise pollution and impact on marine life from returning astronauts to the Moon, landing satellites on Mars (from angering or obliterating indigenous lifeforms), and the environmental impact of leaving lunar and Martian bases.

Collision and Debris Avoidance in Space

The space age, while comparatively recent, has already seen its fair share of litigation, the outcomes of which have both shaped and been shaped by the law of the cosmos. Many of the few cases to date have focused on liability, addressing whether a party is liable for damages that arise in the operation of its spacecraft.

In 1997, a panel of the Court of Arbitration for Space Activities (CASA) decided the first-ever dispute to be litigated under the Convention on Registration of Objects Launched into Outer Space in a case arising out of the collision of US and Russian spacecrafts. In 1981, the US government launched the "Defunct" spacecraft into orbit around Earth, then deactivated it two years later leaving it to decay back through Earth’s atmosphere. In 1996, the Russian spacecraft Cosmos 1805 strayed from its prescribed orbit, collided with the Defunct, and discharged more than 100 fragments of the Defunct’s matter into space. After attempting unsuccessfully to contact the US for a settlement, Russia filed suit with the CASA panel for reimbursement under Article 7 of the Liability Convention. Article 7 is a strict liability provision that requires that the State-party launching a space object is liable for damage to another State-party’s spacecraft. The CASA panel agreed with Russia. Even though the Russian spacecraft was strictly liable for the damage that it caused, the panel found the US had a responsibility to exercise reasonable caution in maintaining its Defunct spacecraft along a safe trajectory. The panel said that, because the US had failed to do so, it was equally liable for the damages to the Russian craft and to other parties who were also exposed to risks presented by the now-defunct spacecraft. Although the Defunct was never meant to be a space debris hazard for other parties, the panel’s finding clarified the Lack of Control Doctrine – which provides for liability even after a State-party recovers control of its orbital debris – and the Continuous Operations Doctrine, which imposes a duty of care to other States-parties to take reasonable precautions in operating a spacecraft. In response to the incident in this case and other similar incidents that occurred after the signing of the Liability Convention, the Inter-Agency Space Debris Coordination Committee (IADC) convened to address the growing problem. Full members of the IADC include more than 20 different space agencies from around the world, including NASA from the US, and the coordination committee has played a major role in advancing international legal protocols that address space debris. The IADC promulgated the "Space Debris Mitigation Guidelines," which detail standards that State-parties should adopt in the prevention, mitigation, and remediation of space debris. In the Space Debris Mitigation Guidelines, the IADC recommends legal standards that assure "safe orbital insertion and deployment," "removal of space objects that are no longer in operational or useful orbits," "safe re-entry projection," "removal and trajectory disposal" and "spacecraft operations designed to minimize break-up probability during operations." The guidelines also detail overlapping and interdependent interests that the space-faring nations should recognize in avoiding space debris.

The Future of Space Law

Space tourism is one of the most high-profile manifestations of the commercial sector’s exploration of outer space. The possible legal issues raised by such ventures alone could come to dominate the future of space law, in light of the relatively small number of private space missions that have already taken place. However, other emerging trends in the nascent field of private-sector space exploration also carry the potential to dictate its future.

Among the most potential legal issues surrounding space activities are space debris, a controversial issue in international space law for decades. Again, these issues are largely theoretical at this stage, but a more visible and aggressive private industry will only serve to make them more pressing.

As the number of private missions continue to increase, and international space law develops, arguably more pressing will be the need for a coherent system of space property rights. The Outer Space Treaty is expressly silent on this issue , and has no framework or mechanism for adjudicating property claims. By contrast, the Moon Treaty, which entered into force in 1976, sought to establish certain guidelines for the use and ownership of such resources. What’s more, the efficacy of the Moon Treaty has been repeatedly called into question. Ironically, the very developments that some argue lend the treaty additional strength (that there is now a growing commercial interest in space and space resources) likely foretell it being left behind in history.

If the Outer Space Treaty ends up dictating the future of private-sector space activities, then that future may be hampered by its near-total ban on private property rights in all celestial bodies. The Moon Treaty, on the other hand, may actually serve as a baseline of sorts for the future, if only by the sheer fact of its existence. However, if early-adapter states in a burgeoning industry see value in space property rights, then future developments may ultimately outstrip the current state of international space law altogether.